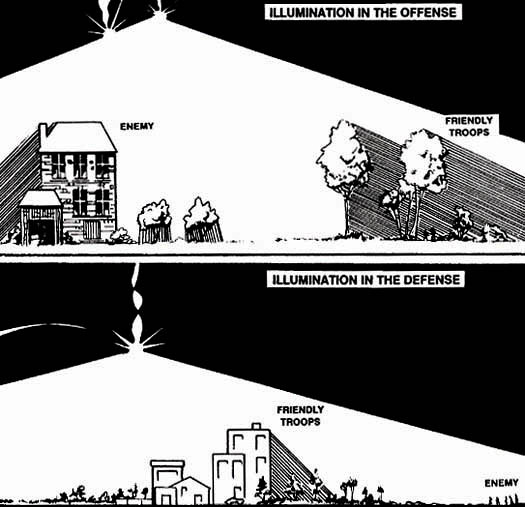

The diagram below explains two simple lighting strategies for use during "military operations on urban terrain," or MOUT, taken from the U.S. Army's Infantryman's Guide to Combat in Built-Up Areas. While there is nothing particularly surprising about an army using light to its advantage, a number of interesting things arise when considering weapons from the perspective of their optical effects.  [Image: "Trip flares, flares, illumination from mortars and artillery, and spotlights (visible light or infrared) can be used to blind [the] enemy... or to artificially illuminate the battlefield," from An Infantryman's Guide to Combat in Built-Up Areas].

[Image: "Trip flares, flares, illumination from mortars and artillery, and spotlights (visible light or infrared) can be used to blind [the] enemy... or to artificially illuminate the battlefield," from An Infantryman's Guide to Combat in Built-Up Areas].

In another army field manual, for instance, called Tactical Employment of Mortars, the practice of running "illumination missions" using "luminous markers" and "specified amounts of illumination ammunition" is explained, such that mortars become less kinetic weapons used in the destruction of buildings than surprise lighting effects—decentralized chandeliers, so to speak, hurled down from above at high speed.

Indeed, "medium and heavy mortars can provide excellent illumination over wide areas," whereas with lighter rounds "the illumination lasts for about 25 seconds, and it provides moderate light over a square kilometer. The gunner must adjust the elevation to achieve height-of-burst changes for this round. The best results are achieved with practice."

One of many reasons I mention this here is because I wonder how these techniques could be de-weaponized and used for the purpose of civilian illumination. You visit a small town somewhere in Scandinavia where night's fall is disturbingly total, with no street lights of any kind turning on after the sun has long since set; yet people are still out there milling about, even sitting on public benches with books in hand, as if preparing to read in utter darkness. But then a lightburst flashes in the sky above, burning for half a minute or more; and then another; and another, at odd angles, turning the streets and squares below into stroboscopes of moving geometry; and this continues for hours—strange nets of light popping in the air above you—as the city goes about its unexpected nightlife, illuminated by repurposed mortars fired by a light brigade camped out on the urban fringe.

Finally, any discussion of how urban lighting effects can be militarized reminds me of a stunning scene from Anthony Beevor's retelling of the fall of Berlin during World War II. There, we read of a Russian general who ordered such extraordinary use of spotlights during the Battle of the Seelow Heights that his own soldiers became totally disoriented when the shelling began: massive clouds of smoke and dust rose up into the beams, forming an impenetrable glowing mist that quickly enveloped them, robbing the battlefield of detail. Light came from every direction and no direction at all, in a complete loss of the shadow-casting effects needed to hide their own troops' movement—a failure, we might say, of military chiaroscuro, or the controlled use of shadows during invasion as seen in the diagram, above.

Lưu trữ Blog

-

▼

2010

(3068)

-

▼

tháng 6

(251)

- Burns vs. Slusarski

- Western lynx spider

- Ding Dong, Doorbell Moth!

- Caterpillar troubles

- 9.7.

- Flooded London 2030

- Conditions Report - June 30 2010

- Austria is different

- Guest Post - A not-so Carrie Bradshaw moment

- Känslor

- Böcker

- Painting around this year's finches

- Porch light spiderlings

- Attack of the destroyers

- Baby Origami - Fold that Baby for Free!

- Well I didn’t think of this one

- Western States 2010

- House-in-a-House Museum

- Frostbite Symptoms and Treatment

- Lång dag

- And here comes the Fun Police...........

- Rat Bait Falls from Helicopter onto Kakapo Island

- Något nytt, något rött och något skogigt

- I love the smell of napalm in the morning

- Top-Managed Belays

- Portable Lensed Microcosms Looking Down Into a Fro...

- The Out-of-Towner

- The Perception of Value

- Hello MummyDiaries!

- Jag kan springa!

- July and August Climbing Events

- World Cup USA Party

- Onion Rings

- Peanut Butter Cupcakes with Peanut Butter Swiss Me...

- Playlist - 26th June 2010

- Bortkopplad

- Zale caterpillar?

- What will this turn into?

- Unknown moth

- Laying down flat

- The best size of spider

- Weak Pull: 2010 Topps Oliver Perez

- What will they say about Julia?

- Cave of Kelpius

- Tails up!

- Freshly shed

- You can't see me

- Nobody can be uncheered by a ladybug.

- Weekend Warrior - Videos to get your Stoked.

- I know I promised - but

- iridescent wings

- Double Edition of Saturdays with Saw Hole.

- Image Concrète

- A Design History of Military Airspace

- How Good is that Bolt?

- Trevlig midsommar!

- Money Saving + False Economy + Benefit Giveaway!

- Mysteries of Life

- Beware the Badger's Curse (and Friday Quiz)

- Lunch in The City: June 21-25

- Climbing and Outdoor News from Here and Abroad - 6...

- Tremor

- Australia has a new Prime Minister and she’s a woman!

- Al Rosen to Gregg Jefferies: I heart your stink

- Memo from Mrs Woog

- Apple on a pedestal

- Glass & te

- Conditions Report - June 23 2010

- Från storstan ut på landet

- A Letter To Myself.

- The Baseball Card Blog welcomes a new writer: Mike...

- Is this the worst (best) dive in history?

- The Meadowlands

- WAVVES - KING OF THE BEACH

- The Munter-Mule

- Family Mines and the Basement Zoning Codes of Minn...

- HERZOG - SEARCH

- CRYSTAL CASTLES - CELESTICA

- Cupcake Club: London Bloggers Meetup

- Fuskare

- The Gift that keeps on Taking

- UIAA Responds to Everest Age Restrictions

- The worst film I have ever seen

- It Sucks!

- A WS100 Scouting Report

- Subterranean Builders' Guide

- The Super-Munter

- An exercise in humility

- Week Ending June 20 (WS - 6 days)

- Crypto-Forestry and the Return of the Repressed

- The "star thing that holds the summer"

- Because I got an email tonight...

- Vanilla & Honey Macarons

- Housewife burned in rissoles incident

- PHOTOGRAPHY BY LUKASZ WIERZBOWSKI

- June and July Climbing Events

- The Truth Behind the Snuggie (+ GIVEAWAY!)

- Taste of London 2010

- Playlist - 19th June - 2010

- Latest work

-

▼

tháng 6

(251)