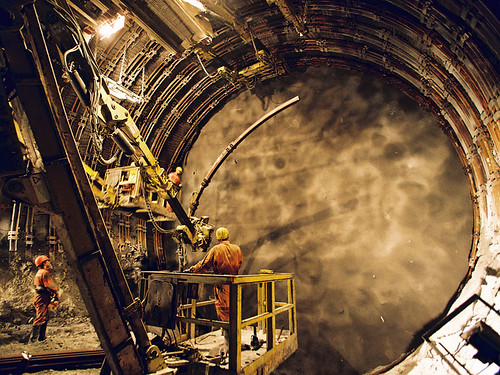

In the underground-themed issue of Rassegna, mentioned earlier, author Nicola Sinopoli offers a brief subterranean builders' guide to bringing architecture underground. "There are now no technological limitations that could stop us from colonizing the underground," he declares, providing a short catalog of useful construction materials in the process.  [Image: The Gotthard Base Tunnel in Sedrun, Switzerland; photo by Brian Fulcher, Walnut, CA, courtesy of Engineering News-Record's 2006 "Year in Construction" recap].

[Image: The Gotthard Base Tunnel in Sedrun, Switzerland; photo by Brian Fulcher, Walnut, CA, courtesy of Engineering News-Record's 2006 "Year in Construction" recap].

Sinopoli's purpose is to point out "some of the new materials that chemistry and physics have offered this new world of construction." And this goes beyond mere drilling equipment—which Sinopoli does not, in fact, cover—to encompass things like high-density buckled polyethylene membranes that are "impervious to organic bacteria and mildews that may be in the ground," and that serve "as an effective barrier against radon, a radioactive gas sometimes found in the earth."

We see flexible geocomposite mats, fiber-optic lighting technologies, a wide variety of grass turf for roofs, and self-ventilating, anti-humidity wall panels, all of which allow "colonizing the underground," as Sinopoli puts it.

- Cases, membranes and buckled plates protect the building from the infiltration of water and roots; woven and non-woven geotextiles, geocomposites, geomats and synthetic monofilaments stabilize and drain the land; and ultra high yield reflective films convey natural light inside the new underground spaces

The idea that "colonizing the underground" will be made possible at least partially through the use of genetically modified plants is pretty fascinating. This extends engineered biologies—future crops and oxygen gardens, perhaps even crypto-forestry—into the earth's subsurface. Speleonauts living inside an architecture of growth chambers three miles underground, shining UV lights at specialty plantlife bred specifically to produce a breathable atmosphere, researching new anthropological directions in the deep.

It's not much of an exaggeration here to say that gardening will be as important to the future of underground living as tunneling equipment.

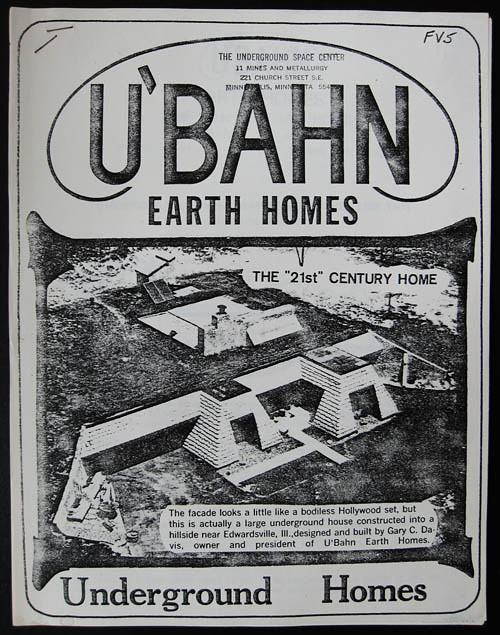

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG of documents in the Underground Space Center Library archive at the Canadian Centre for Architecture].

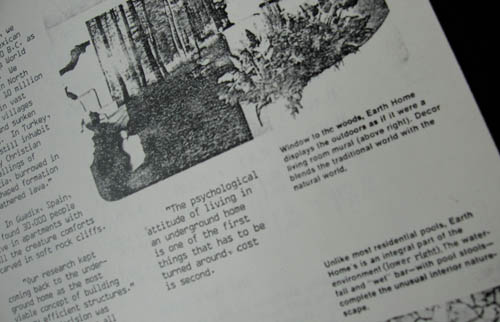

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG of documents in the Underground Space Center Library archive at the Canadian Centre for Architecture].Sinopoli suggests that building underground is, for all intents and purposes, a solved problem: "If anything," he quips, "we should explore what effects living and working in underground or almost underground spaces might have on behavior and quality of life. Sociologists will give their answers to this." This is what I have earlier called psychology at depth, or the unanticipated psychiatric implications of living underground.

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG of documents in the Underground Space Center Library archive at the Canadian Centre for Architecture].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG of documents in the Underground Space Center Library archive at the Canadian Centre for Architecture].I should note, however, that Sinopoli's article is less about moving into scifi mega-cities inside the earth than it is about making things like underground shopping malls and even suburban basements more safe for everyday use. Nonetheless, over-ambitiously applying these same techniques in the outright construction of artificial caverns on a continental scale is, for me, simply too interesting to pass up.

Indeed, I'm reminded of Jeff Long's scifi-horror novel The Descent, in which armed military units lead an invasion of the underworld, heading downward into the earth, Jules Verne-like, but with machine guns, hydroponic agriculture, UV klieg lights, and truckloads of instant concrete. They "approached the subplanet the way America approached manned landings on the moon forty years ago," Long writes, "as a mission requiring life support systems, modes of transportation and access, and logistics." The Army Corps of Engineers gets involved, "tasked to reinforce tunnels, devise new transport systems, drill shafts, build elevators, bore channels, and erect whole camps underground. They even paved parking lots—three thousand feet beneath the surface. Roadways were constructed through the mouths of caves." It takes days at a time to get anywhere in Long's underworld; there are outbreaks of "tropical cave disease," we read, and claustrophobia.

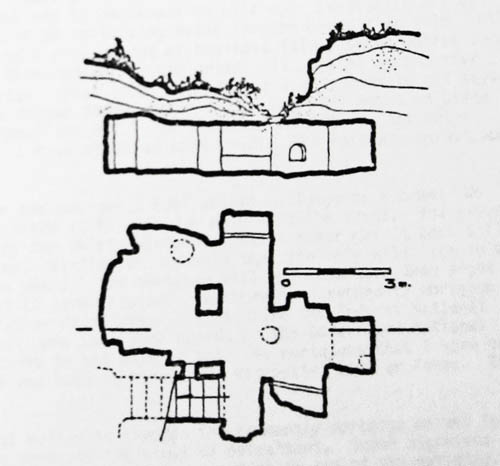

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG of documents in the Underground Space Center Library archive at the Canadian Centre for Architecture].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG of documents in the Underground Space Center Library archive at the Canadian Centre for Architecture].In any case, at this point, Sinopoli suggests, questions of architectural style can re-enter the picture. Indeed, "there are questions about the consequences of underground building on architecture and its language. That's a discussion still waiting to be had."

We can assemble a subterranean builders' guide, in other words, and solve the problem of constructibility; but when it comes to architectural form, if we hope someday to move beyond mere underground shopping malls—for instance, Montreal's overwhelmingly anti-climactic "underground city"—then there is still an awful lot of work to do.

#CCA