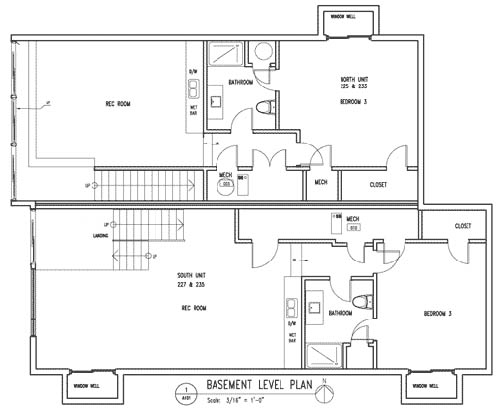

One of many fascinating details in the Underground Space Center Library archives at the Canadian Centre for Architecture is something found in a paper, written by a University of Minnesota law student, called "Zoning Ordinances as Obstacles to Earth Sheltered Housing: A Minnesota Perspective."  [Image: Random basement floorplan].

[Image: Random basement floorplan].

There, amongst other key legal points, the student weighs in on what he calls the "definitional problems" that arise when traditional zoning law is applied to underground space—indeed, "whether zoning regulations apply at all to underground structures."

Though the paper clearly focuses on the state of Minnesota, it goes as far afield as Texas; in the case of Hancox v. Peek, for instance, "a Texas Court of Appeals held that a fallout shelter which was wholly underground, except for a concrete slab which extended a mere two or three inches above the ground, was not a building—merely an appurtenance, and therefore not within the contemplation of a zoning ordinance requiring a minimum distance between buildings and adjacent property." One can easily imagine byzantine courtroom arguments and legal appeals of the future, citing legal precedents from wartime bunker construction, domestic fallout shelters in Texas, and perhaps even subsurface mine-safety regulations in some strange Kafkaesque scenario involving, say, the late Mole Man of Hackney and his contested underground estate.

But, as it happens, my reference to mining safety is deliberate.  [Image: Random basement floorplan].

[Image: Random basement floorplan].

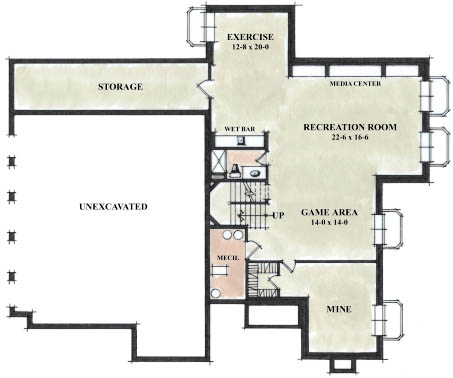

At the time of the paper's writing—the late 1970s—underground facilities, from parking garages to hospitals and private homes, were considered so novel from the perspective of traditional Minnesota zoning law that there was no accepted legal means for how to define or describe them. These are the "definitional problems" mentioned above. "Examples," we read, "are the broad definitions of basement and cellar... defining excavations of greater than 400 cubic yards as 'mining'—thus requiring a special permit, and defining 'detached dwelling' as one 'entirely surrounded by open space'."

That's worth repeating: excavations of greater than 400 cubic yards were legally zoned as mines—whether it was a parking garage or your newly renovated basement rec room.

In other words, if you lived in Minnesota in the 1960s and 70s, and you had a particularly enormous basement, inside of which you and your siblings might have watched television, you could, legally speaking, have been playing inside a mine. Whether or not this gave you permission to harvest minerals is unclear.  [Image: A continuous mining machine at work; image courtesy of Salt Union Ltd].

[Image: A continuous mining machine at work; image courtesy of Salt Union Ltd].

No lawsuit, to my knowledge, has ever been retroactively filed against Minnesotan parents, accusing them of mine-safety violations—but there is always a first time.

Nor has the reverse of this scenario—in which a Minnesotan industrial minerals magnate from St. Cloud successfully rezones his mine or quarry as a domestic basement—been, to my knowledge, attempted.

#CCA

Lưu trữ Blog

-

▼

2010

(3068)

-

▼

tháng 6

(251)

- Burns vs. Slusarski

- Western lynx spider

- Ding Dong, Doorbell Moth!

- Caterpillar troubles

- 9.7.

- Flooded London 2030

- Conditions Report - June 30 2010

- Austria is different

- Guest Post - A not-so Carrie Bradshaw moment

- Känslor

- Böcker

- Painting around this year's finches

- Porch light spiderlings

- Attack of the destroyers

- Baby Origami - Fold that Baby for Free!

- Well I didn’t think of this one

- Western States 2010

- House-in-a-House Museum

- Frostbite Symptoms and Treatment

- Lång dag

- And here comes the Fun Police...........

- Rat Bait Falls from Helicopter onto Kakapo Island

- Något nytt, något rött och något skogigt

- I love the smell of napalm in the morning

- Top-Managed Belays

- Portable Lensed Microcosms Looking Down Into a Fro...

- The Out-of-Towner

- The Perception of Value

- Hello MummyDiaries!

- Jag kan springa!

- July and August Climbing Events

- World Cup USA Party

- Onion Rings

- Peanut Butter Cupcakes with Peanut Butter Swiss Me...

- Playlist - 26th June 2010

- Bortkopplad

- Zale caterpillar?

- What will this turn into?

- Unknown moth

- Laying down flat

- The best size of spider

- Weak Pull: 2010 Topps Oliver Perez

- What will they say about Julia?

- Cave of Kelpius

- Tails up!

- Freshly shed

- You can't see me

- Nobody can be uncheered by a ladybug.

- Weekend Warrior - Videos to get your Stoked.

- I know I promised - but

- iridescent wings

- Double Edition of Saturdays with Saw Hole.

- Image Concrète

- A Design History of Military Airspace

- How Good is that Bolt?

- Trevlig midsommar!

- Money Saving + False Economy + Benefit Giveaway!

- Mysteries of Life

- Beware the Badger's Curse (and Friday Quiz)

- Lunch in The City: June 21-25

- Climbing and Outdoor News from Here and Abroad - 6...

- Tremor

- Australia has a new Prime Minister and she’s a woman!

- Al Rosen to Gregg Jefferies: I heart your stink

- Memo from Mrs Woog

- Apple on a pedestal

- Glass & te

- Conditions Report - June 23 2010

- Från storstan ut på landet

- A Letter To Myself.

- The Baseball Card Blog welcomes a new writer: Mike...

- Is this the worst (best) dive in history?

- The Meadowlands

- WAVVES - KING OF THE BEACH

- The Munter-Mule

- Family Mines and the Basement Zoning Codes of Minn...

- HERZOG - SEARCH

- CRYSTAL CASTLES - CELESTICA

- Cupcake Club: London Bloggers Meetup

- Fuskare

- The Gift that keeps on Taking

- UIAA Responds to Everest Age Restrictions

- The worst film I have ever seen

- It Sucks!

- A WS100 Scouting Report

- Subterranean Builders' Guide

- The Super-Munter

- An exercise in humility

- Week Ending June 20 (WS - 6 days)

- Crypto-Forestry and the Return of the Repressed

- The "star thing that holds the summer"

- Because I got an email tonight...

- Vanilla & Honey Macarons

- Housewife burned in rissoles incident

- PHOTOGRAPHY BY LUKASZ WIERZBOWSKI

- June and July Climbing Events

- The Truth Behind the Snuggie (+ GIVEAWAY!)

- Taste of London 2010

- Playlist - 19th June - 2010

- Latest work

-

▼

tháng 6

(251)